INTRODUCTION:

The world is cruel, the world is unfair. That is what people say, to either comfort or to apathetically justify their lack of success and/or luck. But we need to make the world better.

And for that, we need justice. However, what even is justice? Part of goal 16 of the United Nations Organization, discussing peace, justice, and strong institutions, justice is a vague moral catch-all phrase for what’s good. Most people most likely want the world to be just, but right now it is not. In this paper, we will discover moral philosophies of justice, mix and match them together, discuss forms of government, then apply morals to government.

SECTION 1: How Should We Act?

Justice requires morals. To make a truly just government, we need to first establish a baseline of right and wrong, so that the government can act upon those ideas. In this section of the paper, we will establish and explore different moral philosophies to build a base of morals for society.

- ARISTOTLE: Who Deserves What

One of the first moral theories ever synthesized was Aristotle’s theories on Telos and Balance. Aristotle, as I’m sure many of you reading this have heard of, was a Greek philosopher and the pupil of Plato. He made many contributions to philosophy, but we will only be exploring his ideas on morality. According to Aristotle, justice, and thereby morality was teleological. By this, he meant that morals were based on the original purpose of an object (Sandel). As an example, suppose we are distributing flutes. Who should get the best ones? Well, “according to Aristotle, the best flute players should” (Sandel). This is quite obvious to many of us, giving the best flutes to the best players will produce the best music, and with all the effort the professional flute players put into their art, of course, the best players deserve the best flutes. However, this was not Aristotle’s reason. He thought that the best flutes should go to the best flute players “because that’s what flutes are for—to be played well” (Sandel). Since the purpose, the telos, of the flutes is to be played well, the only moral option in this scenario is to give the best flutes to the best players (Sandel).

Another one of Aristotle’s doctrines is his idea of the Golden Mean. According to Aristotle, “every virtue lies in between two extremes” (Warburton). Essentially, you need to have the right amount of a trait, not too much, not too little. Very similar to the goldilocks story, is it not? Just like in the goldilocks story, everything needs to be just right. The porridge can’t be too hot, nor too cold, the bed cannot be too soft, nor too large, and on and on and on. Another example can be shown from the idea of battle. Take the idea of courage in battle: “A foolhardy person has no concern whatsoever for his safety. He might rush into a dangerous situation when not needed…but that’s not true bravery, only reckless risk-taking. At the other extreme, a cowardly soldier can’t overcome his fear enough to act in an appropriate way” (Warburton). However, a brave person feels fear but beats it to take (Warburton). That, according to Aristotle, was the difference between a virtuous person and a person that was not. In summary, Aristotle’s moral theory is about fulfilling the ‘Telos’ of social practice and about finding a balance.

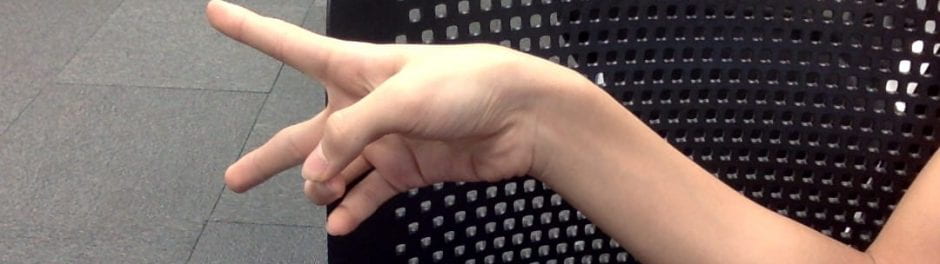

Figure 1 The Virtue Continuum; source

2. Bentham: Happiness as Justice

Figure 2 The Utility Equation; Source

Another great moral philosopher, Jeremy Bentham was focused on the idea of Utility. Utilitarianism “may be defined as the thesis that an act is right or good if it produces pleasure , and evil if it leads to pain” (“Jeremy Bentham”). What Bentham means by this is quite simple. Something is good only if it produces pleasure, and something is evil if it deprives someone of pleasure or gives them pain. Utilitarianismcan be equated to an equation: the righteousness of an act equals pleasure multiplied by the total time the pleasure was present multiplied by the number of people experiencing pleasure derived from that act, minus the total pain produced (Sandel). This is one of the simplest moral philosophies we will be covering. Let’s use an example: the trolley dilemma. The trolley dilemma, or the runaway train problem, is a common ethics problem. Say there is a train that cannot stop. There are five people in the way, and all will die if the train runs into them. However, you are standing next to a lever that, if pulled, will make the train move onto a different track with only one person. According to utilitarianism, you should always pull the lever, as it minimizes death (pain), and maximizes life (pleasure). That, in essence, is Jeremy Bentham’s philosophy.

3. Kant: What Matters is the Motive

Immanuel Kant’s ideas of morality differ wildly from the ones we have covered above. Kant’s ethics are based on 3 notions: The Categorical imperative, Autonomy vs. heteronomy, and treating people as an end in themselves (Sandel).

First, let’s cover his ideas on the categorical imperative. A categorical imperative is a “universal ethical principle stating that one should always respect the humanity in others and that one should only act in accordance with rules that could hold for everyone” (Jankowiak). In understandable terms, what Kant means is that you should never do something if it wasn’t universally applicable. For example, you should not steal. This is obvious to us, and we all know it. But let’s think in Kantian terms for a moment. Why is stealing wrong? Well according to the ‘universal imperative,’ stealing is wrong because, if everybody did it, all trust will break down, and then all of society would follow (Sandel). The easiest way to describe Kantian ethics would simply be: “what if everybody did it?” Quite a lot of words for a simple topic. Additionally, Kant said that ethics are a part of the reason, not emotion, hence “all rational creatures are bound by the same moral law” (Jankowiak). Kant’s solution is based around universalizing situations and solutions. If the action isn’t universal, it is never right.

Another one of Kant’s ideas is his idea of autonomy. What Kant means by autonomy is ‘are you choosing to do this?’, as opposed to heteronomy, where outside forces are coercing you into doing an act (Warburton). I am not responsible for that death: “since there is no autonomy, there can be no moral responsibility” (Sandel). Kant’s third pillar of ethics is directly related to this idea of autonomy. Essentially, to be autonomous is to be held accountable by a law I give myself, or a categorical imperative, “And the categorical imperative requires that I treat all persons with respect—as an end, not merely as a means” (Sandel). Let’s use the example of casual sex. Kant strongly objected to casual sex “on the grounds that it is degrading and objectifying to both partners. Casual sex is objectionable, he thinks, because it is all about the satisfaction of sexual desire, not about respect for the humanity of one’s partner” (Sandel). Simply put, casual sex is not moral as it treats another person as a means or a tool to the end of pleasure. These three pillars of motive, autonomy, and humanity as an end make up Kant’s ethical principle.

4. Rawls: Equality, Equality, Equality

John Rawls was an English philosopher whose ideas of morality focused mostly on equality. He thought that, with logical thinking, rational people would eventually find that an equal state was best. Consider a thought experiment. We gather many people to make laws. However, all these people don’t know who they are while they are inside of this ‘black box’ making the laws. Essentially, “if no one knew anything about themselves, we would choose, in effect, from an original position of equality. Since no one would have a superior bargaining position, the principles we agreeto would be just” (Sandel). Rawls thought that this thought experiment would birth two main principles. The first would let everyone have basic liberties, like freedom of speech and religion. The second would be about social and economic equality (Sandel). If the people in the black box didn’t know what their situation would be after making the laws, people would most likely produce laws that would benefit them, no matter if they were black or white, rich or poor, ugly or beautiful (Warburton). Rawls mostly focused on equality, and how it is right, much like Marx, whom we discuss next.

5. Marx: COMMUNISM

Karl Marx was one of the most influential philosophers of the 19th century, with ideas centralizing equality, communism, and revolution.

According to Marx, the whole of history was a clash between the rich bourgeoisie and the working proletariat (Warburton). In Marx’s viewpoint, the workers of the world were alienated from who they were as actual human beings. Additionally, the harder the exploited workers worked, the moremoney they produced for the capitalists (Warburton). Due to this exploitation and injustice leveed upon the proletariat, Marx arrived at a rather violent conclusion. The time bomb that was the working class was destined to explode and “take over in a violent revolution. Eventually from all this bloodshed a better world would emerge” (Warburton). This future would be a communistic world. In this type of society, people would provide what they could, and society would provide what they needed: “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs” (Marx). To realize this ideal society, Marx called for a revolution of the workers in his Communist Manifesto with his famous words: “The workers of the world have nothing to lose but their chains. Workers of the world, unite!” (Marx). Marx’s ideas of a perfect world boiled down to giving what you can and receiving what you need.

SECTION 2: Modifying Ethics

Of course, no moral theory will be perfect. So, why not combine parts of different ethical theories to fill out the missing parts of some moral theories?

6. The Mixing Bowl

Combining moral theories requires us to put in only parts of whole theories, as some will contradict each other, while some can complete others. Much like cooking, you must work in parts. The first is utilitarianism. As a recap, utilitarianism is the doctrine that “may be defined as the thesis that an act is right or good if it produces pleasure, and evil if it leads to pain” (“Jeremy Bentham”). This is the single most simple doctrine, and so it can be applied to many moral syntheses. It is also instinctively good; more pleasure is better, at least in most people’s minds. Combine this with the most agreeable part of Kantian thinking, where Kant describes that an action can only be right or wrong when it is autonomous, and we have ourselves a philosophy amalgam. However, there is one more combination of doctrines that go together near perfectly, which we will discuss next.

7. An Egalitarian Paradise

We’ve discussed many moral philosophies, but as I’m sure some of you have noticed, two fit together very nicely: Marx’s communism and Rawls’ equality. These two doctrines both describe a world where people are equal, with the largest difference between them being equality being less economically centered than communism. Combining the aspects of equality of the two, while leaving out the fanatical violence of communism gives us a world where there is a centralized distribution system, like taxes, that would try and maximize equality among citizens. Additionally, this world would most likely give citizens basic liberties as part of the Rawlsian component (Sandel). This is the idea of a perfectly equal society, but none ofwhat we’ve previously discussed relates to a country. So, next, we will be discussing government.

PART 3: An Ethical Government

We have discussed the ethics part of an ethical government, but we are still missing the ‘government’ part. So, this next part will be all about government and how ethics applies to it.

8. The Best Form of Government

Now, the government comes in many forms, but we must decide on a form of it that best fits with ethical theory. Government can be split into two basic forms: autocracy, where one party or person has most of the power, and democracy, where the people hold power. Anarchy does not count, as it is just a lack of government. Traditionally, democracy has been seen as more ‘right’ than autocracy; however, this is wrong. Autocracy has a stigma placed upon it due to rulers abusing their power and committing atrocities, a stigma made by people like Hitler. In fact, for ethical applications, autocracy is better than democracy. Centralized power is better for applying moral theories, as it can be universally applied much easier than with democracy. A dictator decreeing that all his citizens must follow this moral philosophy is faster and more effective than having to collect and count votes and manipulating public opinion like with democratic processes. However, autocracy has humans at the top, and as Lord Acton has written, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” (Acton). The reason autocracy doesn’t work is that humans are imperfect. We will talk about solutions to this next, but for now, the form of government that will be synthesized with moral theory is an uncorrupting autocracy.

9. Perfecting Autocracy

As we’ve discussed above, autocracy is imperfect because humans are imperfect, but this can be fixed. Since humans are imperfect and corruptible, just remove the human aspect of autocracy, and we have an incorruptible autocracy. This may seem unreasonable, but with the advent of computers, it has become reasonable to think about (Harari). Computers can only stick to an algorithm, no corruption, not influenceable in any way. Say we have an autocracy that is built upon the thinking of Marx’s communism. This form of the country only works with a central power taking and redistributing wealth and goods. With a human central power, this system does not work. Corruption starts to influence the central power, and the autocratic central power that was working for the people becomes tyranny. A perfect example of this is the USSR. And as anyone who has studied history knows, that did not work out well. However, with a computer as the central power, the redistribution of wealth is much simpler (Harari). With a computer programmed to take wealth and goods and evenly distribute them, we know that the redistribution would be fair and even. With a computerized autocracy programmed around equality, an equal society is an equation and a click away. Nowadays, with credit cards and digital banks instead of actual paper money, the redistribution is even simpler. Just get the computer connected to the central bank, and money is now spread out evenly. That is how you perfect autocracy.

Figure 3 Lenin’s Red Terror; Source

PART 4: A Perfect Government?

We’ve discussed all parts of an ethical government and theorized about applying parts of each doctrine to a state. But how does all of this relate to the real world? That is what we will discuss next.

10. Making a Government

Now, making a government is hard, and it requires many different factors to all go right. However, we will only discuss the material factors in making a government. There are a couple of options. First, revolution. Like Marx’s idea has said, violence can shape a world (Marx). While stirring up a revolution may not be very simple, once the revolution gets going, it is quite simple to make a new government. However, this situation is not ideal. First, a revolution often leads to war, and war leads to pain. Additionally, a revolution often replaces tyranny with tyranny, which we are trying to avoid. However, let’s say the revolution will lead to an ideal world. What would these government laws look like under different moral theories?

11. Example Laws

Once a government is established, we need laws. But what would these laws look like? In this section, we will take issues and laws debated in the real world and apply the moral theories we’ve learned about to them. First up on the chopping block is the issue of abortion. Now abortion is a touchy subject, but applying different moral theories allows us to dodge some controversy and lets us see if these issues are ethical. Abortion in the eyes of utility is not much. Does it make the person getting the abortion happy, while also not giving the people around the person getting abortion pain? If yes, then abortion is completely passable. However, from Aristotle’s standpoint, abortion isn’t as straightforward. First, we need to know the purpose of the female sex in general. In some people’s eyes, the female sex was created to birth children. If this is true, then abortion denies Telos, or the purpose, of women. This was what Aristotle thought (Sandel, Warburton). However, this answer completely depends upon what society thinks the purpose of women to be. From a Kantian perspective, as established above, what matters is still the motive. Why does someone want an abortion? Is it because they don’t want to deal with the economic and social burden that is a child? If so, then abortion is not just. However, if it is to protect other people, then it may be just.

Another topic that is hotly debated in the political world is homosexual marriage. Yet again, from a teleological perspective, it depends on the purpose of marriage and humans in general. If a human’s key purpose is to reproduce, then no, homosexuality would not be just. However, if a human’s purpose is to experience happiness, then homosexuality is perfectly fine. Similarly, if the purpose of marriage is just to bind two humans together, then it would not matter if both partners were of the same gender. From a utilitarian perspective, homosexual marriage and homosexuality are perfectly fine. It gives happiness to those who are homosexual, and it does not hurt anyone to be homosexual. Kant’s philosophy also agrees on this matter. If both participants are marrying out of respect for the other’s humanity, and if no casual sex happens, Kantian ethics allows for homosexuality. By applying differing moral theories to different moral dilemmas, we can see what a state built around these same philosophies would allow as legal and illegal.

CONCLUSION

To find what is right and wrong, we need definitions of justice, need ethics of governments, and need to apply these found definitions of morality to government and modern moral dilemmas. While there is no single right moral philosophy, we can still imagine what the world would be like under them, even with some subpar explaining and grossly simplified explanations. And so, maybe the world, acting upon these ethics, can make the future a place that is less unfair, less cruel to the humans, living in it.

Works Cited

Acton, John Dalberg. Letter to Mandell Creighton. 5 Apr. 1887, Hanover College, London: Macmillan, Letter to Bishop Mandell Creighton. Manuscript.

Harari, Yuval Noah, and Derek Perkins. Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. Unabridged. ed., Place of publication not identified, HarperCollins, 2017.

Jankowiak, Tim. “Kant, Immanuel.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu/kantview/#:~:text=Kant’s%20ethics%20are%20organized%20around,that%20could%20hold%20for%20everyone. Accessed 16 May 2022.

“Jeremy Bentham.” Encyclopedia of World Biography Online, Gale, 1998. Gale In Context: Middle School, link.gale.com/apps/doc/K1631000593/MSIC?u=cnisbj&sid=bookmark-MSIC&xid=d90de2fb. Accessed 9 May 2022.

Marx, Karl, 1818-1883. The Communist Manifesto. London ; Chicago, Ill. :Pluto Press, 1996.

Marx, Karl, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir I. Lenin, and E Czobel. Critique of the Gotha Programme. New York: International Publishers, 1970. Print.

Sandel, Michael J. Justice. New York City, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009.

Warburton, Nigel. A Little History of Philosophy. Yale UP, 2012.

Wenar, Leif, “John Rawls”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/rawls/>.